Data Manipulation with dplyr

Data analysis involves a large amount of janitor work – munging and cleaning data to facilitate downstream data analysis. This lesson demonstrates techniques for advanced data manipulation and analysis with the split-apply-combine strategy. We will use the dplyr package in R to effectively manipulate and conditionally compute summary statistics over subsets of a “big” dataset containing many observations.

This lesson assumes a basic familiarity with R and data frames.

Review

Our data

We’re going to use the yeast gene expression dataset described on the data frames lesson. This is a cleaned up version of a gene expression dataset from Brauer et al. Coordination of Growth Rate, Cell Cycle, Stress Response, and Metabolic Activity in Yeast (2008) Mol Biol Cell 19:352-367. This data is from a gene expression microarray, and in this paper the authors are examining the relationship between growth rate and gene expression in yeast cultures limited by one of six different nutrients (glucose, leucine, ammonium, sulfate, phosphate, uracil). If you give yeast a rich media loaded with nutrients except restrict the supply of a single nutrient, you can control the growth rate to any rate you choose. By starving yeast of specific nutrients you can find genes that:

- Raise or lower their expression in response to growth rate. Growth-rate dependent expression patterns can tell us a lot about cell cycle control, and how the cell responds to stress. The authors found that expression of >25% of all yeast genes is linearly correlated with growth rate, independent of the limiting nutrient. They also found that the subset of negatively growth-correlated genes is enriched for peroxisomal functions, and positively correlated genes mainly encode ribosomal functions.

- Respond differently when different nutrients are being limited. If you see particular genes that respond very differently when a nutrient is sharply restricted, these genes might be involved in the transport or metabolism of that specific nutrient.

You can download the cleaned up version of the data at the link above. The file is called brauer2007_tidy.csv. Later on we’ll actually start with the original raw data (minimally processed) and manipulate it so that we can make it more amenable for analysis.

Reading in data

We need to load both the dplyr and readr packages for efficiently reading in and displaying this data. We’re also going to use many other functions from the dplyr package. Make sure you have these packages installed as described on the setup page.

# Load packages

library(readr)

library(dplyr)

# Read in data

ydat <- read_csv(file="data/brauer2007_tidy.csv")

# Display the data

ydat

# Optionally, bring up the data in a viewer window

# View(ydat)## # A tibble: 198,430 x 7

## symbol systematic_name nutrient rate expression bp mf

## <chr> <chr> <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> <chr>

## 1 SFB2 YNL049C Glucose 0.05 -0.24 ER to Golgi transport molecular function unknown

## 2 <NA> YNL095C Glucose 0.05 0.28 biological process unknown molecular function unknown

## 3 QRI7 YDL104C Glucose 0.05 -0.02 proteolysis and peptidolysis metalloendopeptidase activity

## 4 CFT2 YLR115W Glucose 0.05 -0.33 mRNA polyadenylylation* RNA binding

## 5 SSO2 YMR183C Glucose 0.05 0.05 vesicle fusion* t-SNARE activity

## 6 PSP2 YML017W Glucose 0.05 -0.69 biological process unknown molecular function unknown

## 7 RIB2 YOL066C Glucose 0.05 -0.55 riboflavin biosynthesis pseudouridylate synthase activity*

## 8 VMA13 YPR036W Glucose 0.05 -0.75 vacuolar acidification hydrogen-transporting ATPase activity, rotationa…

## 9 EDC3 YEL015W Glucose 0.05 -0.24 deadenylylation-independent dec… molecular function unknown

## 10 VPS5 YOR069W Glucose 0.05 -0.16 protein retention in Golgi* protein transporter activity

## # … with 198,420 more rowsThe dplyr package

The dplyr package is a relatively new R package that makes data manipulation fast and easy. It imports functionality from another package called magrittr that allows you to chain commands together into a pipeline that will completely change the way you write R code such that you’re writing code the way you’re thinking about the problem.

When you read in data with the readr package (read_csv()) and you had the dplyr package loaded already, the data frame takes on this “special” class of data frames called a tbl, which you can see with class(ydat). If you have other “regular” data frames in your workspace, the tbl_df() function will convert it into the special dplyr tbl that displays nicely (e.g.: iris <- tbl_df(iris)). You don’t have to turn all your data frame objects into tbl_df objects, but it does make working with large datasets a bit easier.

dplyr verbs

The dplyr package gives you a handful of useful verbs for managing data. On their own they don’t do anything that base R can’t do. Here are some of the single-table verbs we’ll be working with in this lesson (single-table meaning that they only work on a single table – contrast that to two-table verbs used for joining data together, which we’ll cover in a later lesson).

filter()select()mutate()arrange()summarize()group_by()

They all take a data.frame or tbl_df as their input for the first argument, and they all return a data.frame or tbl_df as output.

filter()

If you want to filter rows of the data where some condition is true, use the filter() function.

- The first argument is the data frame you want to filter, e.g.

filter(mydata, .... - The second argument is a condition you must satisfy, e.g.

filter(ydat, symbol == "LEU1"). If you want to satisfy all of multiple conditions, you can use the “and” operator,&. The “or” operator|(the pipe character, usually shift-backslash) will return a subset that meet any of the conditions.

==: Equal to!=: Not equal to>,>=: Greater than, greater than or equal to<,<=: Less than, less than or equal to

Let’s try it out. For this to work you have to have already loaded the dplyr package. Let’s take a look at LEU1, a gene involved in leucine synthesis.

# First, make sure you've loaded the dplyr package

library(dplyr)

# Look at a single gene involved in leucine synthesis pathway

filter(ydat, symbol == "LEU1")

# Optionally, bring that result up in a View window

# View(filter(ydat, symbol == "LEU1"))

# Look at multiple genes

filter(ydat, symbol=="LEU1" | symbol=="ADH2")

# Look at LEU1 expression at a low growth rate due to nutrient depletion

# Notice how LEU1 is highly upregulated when leucine is depleted!

filter(ydat, symbol=="LEU1" & rate==.05)

# But expression goes back down when the growth/nutrient restriction is relaxed

filter(ydat, symbol=="LEU1" & rate==.3)

# Show only stats for LEU1 and Leucine depletion.

# LEU1 expression starts off high and drops

filter(ydat, symbol=="LEU1" & nutrient=="Leucine")

# What about LEU1 expression with other nutrients being depleted?

filter(ydat, symbol=="LEU1" & nutrient=="Glucose")Let’s look at this graphically. Don’t worry about what these commands are doing just yet - we’ll cover that later on when we talk about ggplot2. Here’s I’m taking the filtered dataset containing just expression estimates for LEU1 where I have 36 rows (one for each of 6 nutrients \(\times\) 6 growth rates), and I’m piping that dataset to the plotting function, where I’m plotting rate on the x-axis, expression on the y-axis, mapping the value of nutrient to the color, and using a line plot to display the data.

library(ggplot2)

filter(ydat, symbol=="LEU1") %>%

ggplot(aes(rate, expression, colour=nutrient)) + geom_line(lwd=1.5)

Look closely at that! LEU1 is highly expressed when starved of leucine because the cell has to synthesize its own! And as the amount of leucine in the environment (the growth rate) increases, the cell can worry less about synthesizing leucine, so LEU1 expression goes back down. Consequently the cell can devote more energy into other functions, and we see other genes’ expression very slightly raising.

EXERCISE 1

- Display the data where the gene ontology biological process (the

bpvariable) is “leucine biosynthesis” (case-sensitive) and the limiting nutrient was Leucine. (Answer should return a 24-by-7 data frame – 4 genes \(\times\) 6 growth rates). - Gene/rate combinations had high expression (in the top 1% of expressed genes)? Hint: see

?quantileand tryquantile(ydat$expression, probs=.99)to see the expression value which is higher than 99% of all the data, thenfilter()based on that. Try wrapping your answer with aView()function so you can see the whole thing. What does it look like those genes are doing? Answer should return a 1971-by-7 data frame.

Aside: Writing Data to File

What we’ve done up to this point is read in data from a file (read_csv(...)), and assigning that to an object in our workspace (ydat <- ...). When we run operations like filter() on our data, consider two things:

- The

ydatobject in our workspace is not being modified directly. That is, we canfilter(ydat, ...), and a result is returned to the screen, butydatremains the same. This effect is similar to what we demonstrated in our first session.

# Assign the value '50' to the weight object.

weight <- 50

# Print out weight to the screen (50)

weight

# What's the value of weight plus 10?

weight + 10

# Weight is still 50

weight

# Weight is only modified if we *reassign* weight to the modified value

weight <- weight+10

# Weight is now 60

weight- More importantly, the data file on disk (

data/brauer2007_tidy.csv) is never modified. No matter what we do to ydat, the file is never modified. If we want to save the result of an operation to a file on disk, we can assign the result of an operation to an object, andwrite_csvthat object to disk. See the help for?write_csv(note,write_csv()with an underscore is part of the readr package – not to be confused with the built-inwrite.csv()function).

# What's the result of this filter operation?

filter(ydat, nutrient=="Leucine" & bp=="leucine biosynthesis")

# Assign the result to a new object

leudat <- filter(ydat, nutrient=="Leucine" & bp=="leucine biosynthesis")

# Write that out to disk

write_csv(leudat, "leucinedata.csv")Note that this is different than saving your entire workspace to an Rdata file, which would contain all the objects we’ve created (weight, ydat, leudat, etc).

select()

The filter() function allows you to return only certain rows matching a condition. The select() function returns only certain columns. The first argument is the data, and subsequent arguments are the columns you want.

# Select just the symbol and systematic_name

select(ydat, symbol, systematic_name)

# Alternatively, just remove columns. Remove the bp and mf columns.

select(ydat, -bp, -mf)

# Notice that the original data doesn't change!

ydatNotice above how the original data doesn’t change. We’re selecting out only certain columns of interest and throwing away columns we don’t care about. If we wanted to keep this data, we would need to reassign the result of the select() operation to a new object. Let’s make a new object called nogo that does not contain the GO annotations. Notice again how the original data is unchanged.

# create a new dataset without the go annotations.

nogo <- select(ydat, -bp, -mf)

nogo

# we could filter this new dataset

filter(nogo, symbol=="LEU1" & rate==.05)

# Notice how the original data is unchanged - still have all 7 columns

ydatmutate()

The mutate() function adds new columns to the data. Remember, it doesn’t actually modify the data frame you’re operating on, and the result is transient unless you assign it to a new object or reassign it back to itself (generally, not always a good practice).

The expression level reported here is the \(log_2\) of the sample signal divided by the signal in the reference channel, where the reference RNA for all samples was taken from the glucose-limited chemostat grown at a dilution rate of 0.25 \(h^{-1}\). Let’s mutate this data to add a new variable called “signal” that’s the actual raw signal ratio instead of the log-transformed signal.

mutate(nogo, signal=2^expression)Mutate has a nice little feature too in that it’s “lazy.” You can mutate and add one variable, then continue mutating to add more variables based on that variable. Let’s make another column that’s the square root of the signal ratio.

mutate(nogo, signal=2^expression, sigsr=sqrt(signal))Again, don’t worry about the code here to make the plot – we’ll learn about this later. Why do you think we log-transform the data prior to analysis?

library(tidyr)

mutate(nogo, signal=2^expression, sigsr=sqrt(signal)) %>%

gather(unit, value, expression:sigsr) %>%

ggplot(aes(value)) + geom_histogram(bins=100) + facet_wrap(~unit, scales="free")

arrange()

The arrange() function does what it sounds like. It takes a data frame or tbl and arranges (or sorts) by column(s) of interest. The first argument is the data, and subsequent arguments are columns to sort on. Use the desc() function to arrange by descending.

# arrange by gene symbol

arrange(ydat, symbol)

# arrange by expression (default: increasing)

arrange(ydat, expression)

# arrange by decreasing expression

arrange(ydat, desc(expression))EXERCISE 2

- First, re-run the command you used above to filter the data for genes involved in the “leucine biosynthesis” biological process and where the limiting nutrient is Leucine.

- Wrap this entire filtered result with a call to

arrange()where you’ll arrange the result of #1 by the gene symbol. - Wrap this entire result in a

View()statement so you can see the entire result.

summarize()

The summarize() function summarizes multiple values to a single value. On its own the summarize() function doesn’t seem to be all that useful. The dplyr package provides a few convenience functions called n() and n_distinct() that tell you the number of observations or the number of distinct values of a particular variable.

Notice that summarize takes a data frame and returns a data frame. In this case it’s a 1x1 data frame with a single row and a single column. The name of the column, by default is whatever the expression was used to summarize the data. This usually isn’t pretty, and if we wanted to work with this resulting data frame later on, we’d want to name that returned value something easier to deal with.

# Get the mean expression for all genes

summarize(ydat, mean(expression))

# Use a more friendly name, e.g., meanexp, or whatever you want to call it.

summarize(ydat, meanexp=mean(expression))

# Measure the correlation between rate and expression

summarize(ydat, r=cor(rate, expression))

# Get the number of observations

summarize(ydat, n())

# The number of distinct gene symbols in the data

summarize(ydat, n_distinct(symbol))group_by()

We saw that summarize() isn’t that useful on its own. Neither is group_by() All this does is takes an existing data frame and coverts it into a grouped data frame where operations are performed by group.

ydat

group_by(ydat, nutrient)

group_by(ydat, nutrient, rate)The real power comes in where group_by() and summarize() are used together. First, write the group_by() statement. Then wrap the result of that with a call to summarize().

# Get the mean expression for each gene

# group_by(ydat, symbol)

summarize(group_by(ydat, symbol), meanexp=mean(expression))

# Get the correlation between rate and expression for each nutrient

# group_by(ydat, nutrient)

summarize(group_by(ydat, nutrient), r=cor(rate, expression))The pipe: %>%

How %>% works

This is where things get awesome. The dplyr package imports functionality from the magrittr package that lets you pipe the output of one function to the input of another, so you can avoid nesting functions. It looks like this: %>%. You don’t have to load the magrittr package to use it since dplyr imports its functionality when you load the dplyr package.

Here’s the simplest way to use it. Remember the tail() function. It expects a data frame as input, and the next argument is the number of lines to print. These two commands are identical:

tail(ydat, 5)

ydat %>% tail(5)Let’s use one of the dplyr verbs.

filter(ydat, nutrient=="Leucine")

ydat %>% filter(nutrient=="Leucine")Nesting versus %>%

So what?

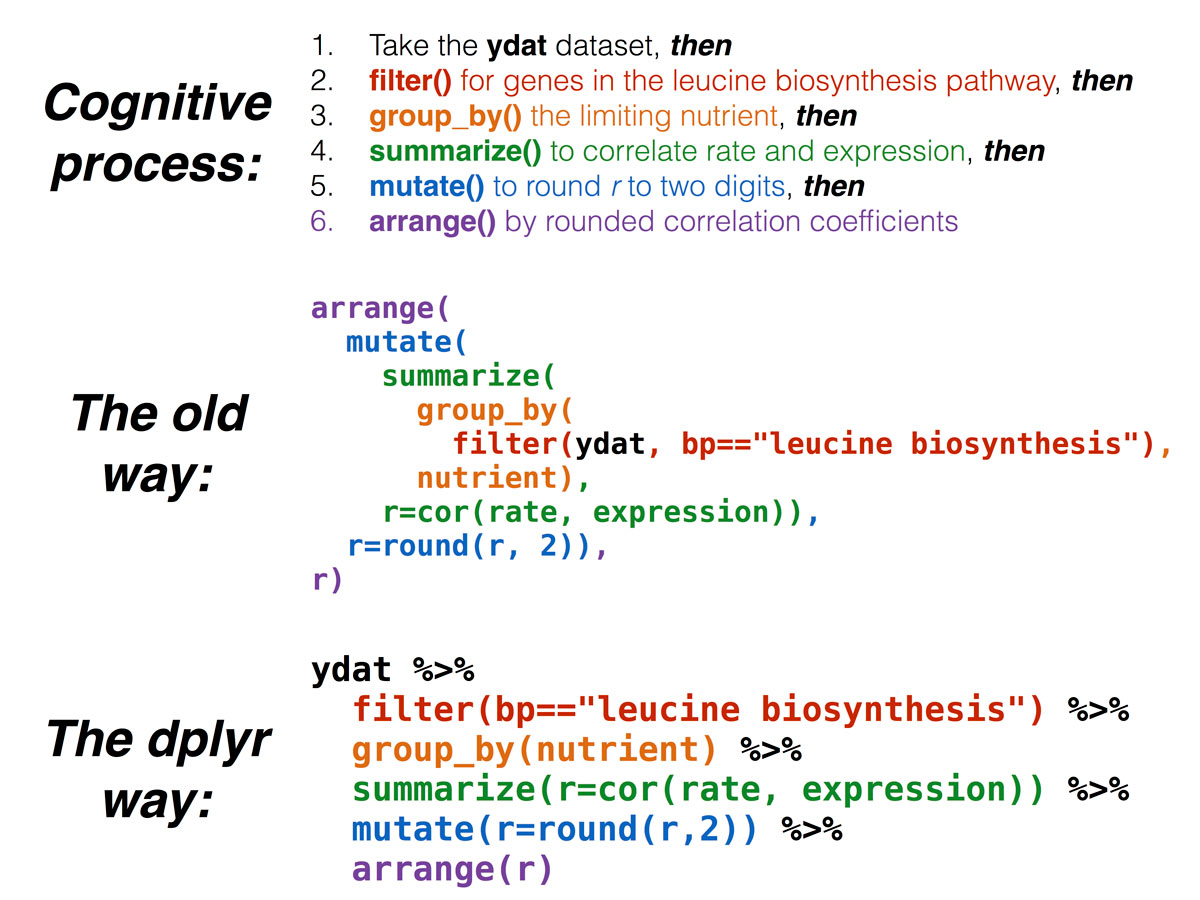

Now, think about this for a minute. What if we wanted to get the correlation between the growth rate and expression separately for each limiting nutrient only for genes in the leucine biosynthesis pathway, and return a sorted list of those correlation coeffients rounded to two digits? Mentally we would do something like this:

- Take the

ydatdataset - then

filter()it for genes in the leucine biosynthesis pathway - then

group_by()the limiting nutrient - then

summarize()to get the correlation (cor()) between rate and expression - then

mutate()to round the result of the above calculation to two significant digits - then

arrange()by the rounded correlation coefficient above

But in code, it gets ugly. First, take the ydat dataset

ydatthen filter() it for genes in the leucine biosynthesis pathway

filter(ydat, bp=="leucine biosynthesis")then group_by() the limiting nutrient

group_by(filter(ydat, bp=="leucine biosynthesis"), nutrient)then summarize() to get the correlation (cor()) between rate and expression

summarize(group_by(filter(ydat, bp == "leucine biosynthesis"), nutrient), r = cor(rate, expression))then mutate() to round the result of the above calculation to two significant digits

mutate(summarize(group_by(filter(ydat, bp == "leucine biosynthesis"), nutrient), r = cor(rate, expression)), r = round(r, 2))then arrange() by the rounded correlation coefficient above

arrange(

mutate(

summarize(

group_by(

filter(ydat, bp=="leucine biosynthesis"),

nutrient),

r=cor(rate, expression)),

r=round(r, 2)),

r)Now compare that with the mental process of what you’re actually trying to accomplish. The way you would do this without pipes is completely inside-out and backwards from the way you express in words and in thought what you want to do. The pipe operator %>% allows you to pass the output data frame from one function to the input data frame to another function.

Nesting functions versus piping

This is how we would do that in code. It’s as simple as replacing the word “then” in words to the symbol %>% in code. (There’s a keyboard shortcut that I’ll use frequently to insert the %>% sequence – you can see what it is by clicking the Tools menu in RStudio, then selecting Keyboard Shortcut Help. On Mac, it’s CMD-SHIFT-M.)

ydat %>%

filter(bp=="leucine biosynthesis") %>%

group_by(nutrient) %>%

summarize(r=cor(rate, expression)) %>%

mutate(r=round(r,2)) %>%

arrange(r)Piping exercises

EXERCISE 3

Here’s a warm-up round. Try the following.

Show the limiting nutrient and expression values for the gene ADH2 when the growth rate is restricted to 0.05. Hint: 2 pipes: filter and select.

What are the four most highly expressed genes when the growth rate is restricted to 0.05 by restricting glucose? Show only the symbol, expression value, and GO terms. Hint: 4 pipes: filter, arrange, head, and select.

When the growth rate is restricted to 0.05, what is the average expression level across all genes in the “response to stress” biological process, separately for each limiting nutrient? What about genes in the “protein biosynthesis” biological process? Hint: 3 pipes: filter, group_by, summarize.

EXERCISE 4

That was easy, right? How about some tougher ones.

First, some review. How do we see the number of distinct values of a variable? Use n_distinct() within a summarize() call.

ydat %>% summarize(n_distinct(mf))Which 10 biological process annotations have the most genes associated with them? What about molecular functions? Hint: 4 pipes: group_by, summarize with n_distinct, arrange, head.

How many distinct genes are there where we know what process the gene is involved in but we don’t know what it does? Hint: 3 pipes; filter where bp!="biological process unknown" & mf=="molecular function unknown", and after selecting columns of interest, pipe the output to distinct(). The answer should be 737, and here are a few:

When the growth rate is restricted to 0.05 by limiting Glucose, which biological processes are the most upregulated? Show a sorted list with the most upregulated BPs on top, displaying the biological process and the average expression of all genes in that process rounded to two digits. Hint: 5 pipes: filter, group_by, summarize, mutate, arrange.

Group the data by limiting nutrient (primarily) then by biological process. Get the average expression for all genes annotated with each process, separately for each limiting nutrient, where the growth rate is restricted to 0.05. Arrange the result to show the most upregulated processes on top. The initial result will look like the result below. Pipe this output to a View() statement. What’s going on? Why didn’t the arrange() work? Hint: 5 pipes: filter, group_by, summarize, arrange, View.

Let’s try to further process that result to get only the top three most upregulated biolgocal processes for each limiting nutrient. Google search “dplyr first result within group.” You’ll need a filter(row_number()......) in there somewhere. Hint: 5 pipes: filter, group_by, summarize, arrange, filter(row_number().... Note: dplyr’s pipe syntax used to be %.% before it changed to %>%. So when looking around, you might still see some people use the old syntax. Now if you try to use the old syntax, you’ll get a deprecation warning.

There’s a slight problem with the examples above. We’re getting the average expression of all the biological processes separately by each nutrient. But some of these biological processes only have a single gene in them! If we tried to do the same thing to get the correlation between rate and expression, the calculation would work, but we’d get a warning about a standard deviation being zero. The correlation coefficient value that results is NA, i.e., missing. While we’re summarizing the correlation between rate and expression, let’s also show the number of distinct genes within each grouping.

ydat %>%

group_by(nutrient, bp) %>%

summarize(r=cor(rate, expression), ngenes=n_distinct(symbol))## Warning in cor(rate, expression): the standard deviation is zeroTake the above code and continue to process the result to show only results where the process has at least 5 genes. Add a column corresponding to the absolute value of the correlation coefficient, and show for each nutrient the singular process with the highest correlation between rate and expression, regardless of direction. Hint: 4 more pipes: filter, mutate, arrange, and filter again with row_number()==1. Ignore the warning.

Homework

Looking for more practice? Try this homework assignment.

Source: https://raw.githubusercontent.com/4va/biodatasci/master/r-dplyr-yeast.Rmd